When Will the Trolley From Upoerline to Tulane Run Again Innew Orleans

| New Orleans Streetcars | |||

|---|---|---|---|

Streetcars on the Canal Street line. | |||

| Operation | |||

| Locale | New Orleans, Louisiana | ||

| Open | September 1835 (steam locomotives and horsecars) February 1893 (electrical streetcars/trams) | ||

| Lines | v operating | ||

| Operator(s) | New Orleans Regional Transit Dominance (RTA) | ||

| Infrastructure | |||

| Rails estimate | five fttwo+ ane⁄2 in (ane,588 mm) Pennsylvania trolley gauge | ||

| Minimum bend radius | 28 ft (8.534 m) in one thousand, l ft (15.24 yard) elsewhere[1] | ||

| Electrification | 600 V DC trolley wire | ||

| Statistics | |||

| Route length | 22.three mi (35.9 km)[two] | ||

| Daily | 21,600[three] | ||

| |||

Streetcars in New Orleans take been an integral part of the city'due south public transportation network since the first one-half of the 19th century. The longest of New Orleans' streetcar lines, the St. Charles Avenue line, is the oldest continuously operating street railway system in the globe.[4] : 42 Today, the streetcars are operated past the New Orleans Regional Transit Authority (RTA).

At that place are currently 5 operating streetcar lines in New Orleans: The St. Charles Avenue Line, the Riverfront Line, the Culvert Street Line (which has two branches), and the Loyola Avenue Line and Rampart/St. Claude Line (which are operated every bit one through-routed line). The St. Charles Avenue Line is the only line that has operated continuously throughout New Orleans' streetcar history (though service was interrupted later Hurricane Katrina in August 2005 and resumed but in role in December 2006, equally noted below). All other lines were replaced past coach service in the period from the late 1940s to the early 1960s. Preservationists were unable to relieve the streetcars on Canal Street, but were able to convince the city government to protect the St. Charles Artery Line by granting it historic landmark condition. In the later on 20th century, trends began to favor runway transit once again. A brusk Riverfront Line started service in 1988, and service returned to Canal Street in 2004, xl years subsequently it had been close downward.[5] : 79, 124

The wide destruction wrought on the city by Hurricane Katrina and subsequent floods from the levee breaches in August 2005 knocked all the streetcar lines out of operation and damaged many of the streetcars. Service on a portion of the Canal Street line was restored in December of that year, with the rest of the line and the Riverfront line returning to service in early 2006. On December 23, 2007, the Regional Transit Authority (RTA) extended service on the St. Charles line from Napoleon Avenue to the terminate of historic St. Charles Avenue (the "Riverbend"). On June 22, 2008 service was restored to the end of the line at South Carrollton Avenue & South Claiborne Artery.

History [edit]

The definitive history of New Orleans streetcars is found in Louis Hennick and Harper Charlton, The Streetcars of New Orleans, [4] which is the source for this summary of New Orleans streetcar history.

Ancestry [edit]

On April 23, 1831, the Pontchartrain Railroad Company (PRR) established the offset rail service in New Orleans along a v-mile line running due north on Elysian Fields Avenue from the Mississippi River toward Lake Pontchartrain. These showtime trains, however, were pulled by horses because the engines had not however arrived from England. The PRR received its outset working steam engine the next year, and first put it into service on September 27, 1832. Service connected in a mixed fashion, running sometimes with locomotives, and at other times with horse traction. A round trip fare at that time was 70-five cents.[iv] : 5

Those first operations included inter-city and suburban railroad lines, and horse-drawn (or mule-drawn) bus lines. (An omnibus is substantially a smaller form of a stagecoach.) The showtime lines of city rail service were created by the New Orleans and Carrollton Railroad, which in 1835 opened three lines. In the offset week of January, the company opened its Poydras-Mag horse-fatigued line on its namesake streets (Poydras Street and Magazine Street), the first true street railway line in the metropolis. New York Metropolis was the but place to precede New Orleans with street railway service. Then a horse-fatigued line to the suburb of Lafayette, which was centered on Jackson Artery, opened on January thirteen. In September, the New Orleans and Carrollton started operating its third line, a steam-powered line along present-day St. Charles Avenue, so called Nayades, connecting the metropolis with the suburb of Carrollton, and terminating virtually the present-twenty-four hour period intersection of St. Charles Avenue and Carrollton Artery. The Poydras-Mag line ceased functioning in March or April 1836, about the time that a new La Course Street line was opened along that street (at present named Race Street). That line ended in the 1840s, but the Lafayette and Carrollton lines continued, somewhen condign the Jackson and St. Charles streetcar lines.[four] : half dozen–7

Every bit the area upriver (uptown) from the city began to be built upwards—much of the new development along the Nayades (St. Charles Avenue) corridor—additional lines were created by the New Orleans and Carrollton. On February 4, 1850, branch lines were opened on Louisiana and Napoleon Avenues. Like the Jackson line, these were horse- or mule-drawn cars, operating from Nayades Artery to the river forth their namesake streets.[four] : eight The Louisiana line was lightly patronized, and was discontinued in 1878. The Napoleon line continued into the next century.[4] : 88–89

Up until about 1860, bus lines provided the only public transit outside the expanse serviced by the New Orleans and Carrollton RR. The need was felt for a truthful citywide street railway service. Toward this end, the New Orleans City RR was chartered on June 15, 1860. The first line, Rampart and Esplanade (subsequently chosen simply Esplanade), opened June 1, 1861, followed in quick succession past the Magazine, Military camp and Prytania (subsequently called Prytania), Canal, Rampart and Dauphine (later Dauphine), and finally Bayou Span and City Park. Despite the beginnings of war, the company opened and connected service on its new lines. A few other efforts were attempted during the Ceremonious War, but progress resumed shortly afterwards the war's finish.[4] : 9–11

In 1866, several boosted street railway companies made their appearance in New Orleans. The first was the Mag Street Railroad Co., which soon merged with the second, the Crescent Urban center Railroad Co. The St. Charles Street Railroad Co. was adjacent, followed in 1867 by the Canal and Claiborne Streets Railroad Co. and in 1868 by the Orleans Railroad Co. The horsecar lines of these companies covered different parts of the urban center, overlapping in some areas. The City RR fifty-fifty operated a steam railroad to Lake Pontchartrain, the West End line, which eventually became part of the urban center streetcar system.[iv] : 12–13

Desegregation protests [edit]

Streetcars in New Orleans had been segregated since they were introduced. A few separate cars marked with stars were designated for black people - the so-called "star auto" organization.

In April 1867, William Nichols got onto a white-simply automobile and was forced out. In the following weeks, thousands of African Americans engaged in protests and some riots bankrupt out. Fearing the repetition of violence seen in previous years, the metropolis, by May viii, desegregated the streetcar organisation. The principal of police told his officers: "Take no interference with negroes riding in cars of whatsoever kind. No passenger, has a right to eject any other passenger, no affair what his color."[6]

The streetcar system remained integrated until 1902.[7]

Horsecar companies and lines operated [edit]

In the late 1800s, these were the streetcar companies and the lines they operated:[iv] : 72

- New Orleans and Carrollton Railroad Co.:

- Carrollton

- Jackson

- Louisiana

- Napoleon

- New Orleans Metropolis Railroad Co.:

- Esplanade

- Canal

- Magazine

- Prytania

- Dauphine

- Bayou Bridge and City Park

- Barracks and Slaughter Firm

- French Market

- Levee and Barracks

- W End

- Crescent Metropolis Railroad Co.:

- Announcement

- Coliseum

- Southward Peters

- Tchoupitoulas

- St. Charles Street Railroad Co.:

- Clio

- Carondelet

- Dryades

- Canal and Claiborne Streets Railroad Co.:

- Claiborne (North)

- Tulane

- Girod and Poydras

- Orleans Railroad Co.:

- Bayou St. John

- Broad

- City Park

- French Market

The coming of electrification [edit]

A number of experiments were tried out over the next few decades in an endeavor to find a improve method than horses or mules for propulsion of streetcars. These included an overhead cablevision automobile system (an cloak-and-dagger cable, such as was eventually developed in San Francisco, was impossible because of the high water table under New Orleans); a walking beam system; pneumatic propulsion; an ammonia locomotive; a "Thermo-specific" arrangement using super-heated h2o; and the Lamm Fireless engine.[4] : 14–xvi Lamm engines were actually adopted and used for a time on the New Orleans and Carrollton line, which had previously used steam locomotives. That line gradually gave upwards steam locomotives because of the objections of residents along the line to the smoke, soot, and noise. The surface area between the town of Carrollton and the City of New Orleans was sparsely populated with big swaths of agronomical country when the line was laid out in the 1830s; past the latter 19th century information technology was almost completely urbanized. Carrollton was annexed to New Orleans in 1874. Due to this increased urbanization, horsecars were used on the entire line.[iv] : 18

Electrical propulsion of streetcars finally won out over all the other experimental methods. Electrical powered streetcars made their first appearance in New Orleans on the Carrollton line on February 1, 1893. The line was also extended out Carrollton Avenue and renamed St. Charles.[4] : 23

Other companies followed suit. Over the next few years, about all the streetcar lines of all six companies were electrified, including the West End steam line; the few lines that remained animal powered, such as the Girod and Poydras, were discontinued.[4] : 23–24, 68–69 Besides, operations of the half-dozen companies began to be consolidated at this time, beginning with formation of the New Orleans Traction Co., which took over performance of the New Orleans Urban center and Lake RR (an 1883 renaming of the New Orleans Metropolis RR) and the Crescent City RR in 1892. New Orleans Traction became the New Orleans City RR in 1899, the second company to employ that name. The Canal and Claiborne company was merged into the New Orleans and Carrollton in 1899. Then in 1902, New Orleans Railways Co. took over operation of all city streetcars, and in 1905 the operating company became New Orleans Railway and Light Co. Terminal consolidation of ownership as well as operation finally became reality in 1922 with the formation of New Orleans Public Service Incorporated (usually abbreviated NOPSI, never NOPS).[four] : 45–46

Electric streetcars under consolidated operation [edit]

Labor problems began to occupy the attention of street railway officials as consolidation progressed. At first, each of the street railway companies had its own agreement with its operating personnel. New Orleans Railways tried to maintain those separate agreements, merely labor representatives insisted on one agreement for the entire company. They also demanded an increase in pay and recognition of their union, Partition 194 of the Amalgamated Association of Street and Electric Railway Employees of America. The matrimony struck on September 27, 1902. After about two weeks of strife, a settlement was reached, and in early 1903, the company signed a contract and recognized the union.[4] : 29

In 1902, there were protests when the Louisiana legislature mandated that public transportation must enforce racial segregation. At first this was objected to past both white and blackness riders as an inconvenience, and by the streetcar companies on grounds of both added expense and the difficulties of determining the racial background of some New Orleanians.

Consolidation of operations under a single company had the advantage of untangling and rationalizing some streetcar lines. Equally an extreme case, consider the Coliseum line, which had the nickname Snake Line, because it wandered all over uptown New Orleans. Its early on name Canal and Coliseum and Upper Magazine gives an idea of the route. Under consolidation, Coliseum was pretty much express to service on its namesake street, with trackage on upper Mag Street turned over to the Mag line, as one might expect. Other efficiencies were instituted, such as reducing the number of streetcar lines operating over long stretches of Canal Street.[four] : fourscore

There was another strike commencement July ane, 1920. This one was settled around the end of July with a new contract.[4] : 36

In the early on 1920s, several extensions and rearrangements of service resulted in the inauguration of the famous Want line, the Freret line, the Gentilly line, and the St. Claude line.[4] : 38

In 1929, at that place was a widespread strike by transit workers demanding amend pay, which was widely supported by much of the public. Sandwiches on baguettes were given to the "poor boys" on strike, said to exist the origin of the local proper noun of "po' boy" sandwiches. There was much rioting and animosity. Several streetcars were burned, and several people were killed. Service was gradually restored, with the strike ending in Oct.[4] : 39

The same year, the last of the 4 fteight+ 1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) standard judge tracks were converted to 5 ft2+ 1⁄2 in (1,588 mm) (Pennsylvania trolley gauge) to match the balance of the streetcar lines.[4] : 196

Buses began to exist used in New Orleans transit in 1924. Several streetcar lines were converted to passenger vehicle or were abandoned outright over the next 15 years. Beginning after Globe State of war Ii, as in much of the United states, almost all streetcar lines were replaced with buses, either internal combustion (gasoline/diesel) or electric (trolley bus). Meet the Historic Lines section below.[4] : 39–40 Track and overhead wire of abandoned or converted lines were generally removed, although remnants of abased track remain in a few places around the urban center.

The concluding four streetcar lines in New Orleans were the S. Claiborne and Napoleon lines, which were converted to motor bus in 1953; the Canal, which was converted in 1964; and the St. Charles, which has continued in operation, and now has historic landmark status.[4] : 42

Racial segregation on streetcars and buses in New Orleans was finally ended peacefully in 1958. Until so, signs separating the races were carried on the backs of the seats in streetcars and buses. These signs could be moved forrad or back in the vehicle every bit passenger loads inverse during the operating twenty-four hour period. Nether court order, the signs were simply removed, and passengers were allowed to sit wherever they pleased.

In 1974, the Amalgamated won a representation ballot and formed Local Partitioning 1560 in New Orleans. Negotiations betwixt the spousal relationship and NOPSI were unsuccessful, and a strike followed. In December 1974, a contract was signed between NOPSI and Local 1560, simply the strike was not completely settled until the following March.[eight]

Streetcars under RTA [edit]

| Streetcars in New Orleans | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organization schematic | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In the late 1970s and early on 1980s, information technology became apparent that individual performance of the New Orleans transit organisation could not continue. Creation of a public torso that could receive revenue enhancement money and authorize for federal funding was necessary. The Louisiana legislature created the New Orleans Regional Transit Say-so (RTA) in 1979, and in 1983, RTA took over buying and functioning of the organization.[5] : 73

In 1988, a new Riverfront line was created, using private right of way along the river levee. This was the get-go new streetcar line in New Orleans since 1926. Then in 2004, the Canal line was reconstructed and restored to track performance.[5] : 79, 124 An all-new line on Loyola Artery was opened in 2013. It was extended beyond Culvert Street on Rampart Street and St. Claude Artery in 2016 in a short form of the historic St. Claude streetcar line.[ix] See the Current Lines and Future Network Expansion sections below.

Hurricane Katrina [edit]

Fallen pole across St. Charles streetcar tracks.

The area through which the St. Charles Artery Line traveled fared comparatively well in Hurricane Katrina's devastating bear on on New Orleans at the end of August 2005, with moderate flooding merely of the ii ends of the line at Claiborne Avenue and at Canal Street. Nevertheless, wind harm and falling trees took out many sections of trolley wire forth St. Charles Avenue, and vehicles parked on the neutral footing (traffic medians) over the inactive tracks degraded parts of the correct-of-way. At the beginning of Oct 2005, every bit this part of town started beingness repopulated, bus service began running on the St. Charles line.

The section running from Culvert Street to Lee Circle via Carondelet Street and St. Charles Street in the Central Business District was restored December xix, 2006 at 10:30 a.m. Central time. Service from Lee Circumvolve to Napoleon Avenue in uptown New Orleans was restored November x, 2007 at 2:00 p.thou. RTA restored streetcar service on the rest of St. Charles Ave. on December 23, 2007. Service along the remainder of the line on Carrollton Ave. to Claiborne Artery resumed June 22, 2008.[10] [eleven] [12] [thirteen] The fourth dimension was needed to repair the damage acquired by Hurricane Katrina and to perform other maintenance and upgrades to the lines that had been scheduled earlier the hurricane. Leaving the line shut down and the electrical arrangement unpowered allowed the upgrades to be performed more than safely and easily.

Maybe more serious was the upshot on the system's rolling stock. The vintage green streetcars rode out the storm in the sealed barn in a portion of Old Carrollton that did not flood, and were undamaged. However, the newer red cars (with the exception of one which was in Carrollton for repair work at the time) were in a different befouled that unfortunately did inundation, and all of them were rendered inoperable; early estimates were that each car would price between $800,000 and $i,000,000 to restore. In December 2006, RTA received a $46 meg grant to aid pay for the car restoration efforts. The showtime restored cars were to be placed in service early in 2009.

Service on the Culvert Street Line was restored in December 2005, with several historic St. Charles line green cars transferred to serve there while the flood-damaged red cars were being repaired. The eventual reopening of all lines was made a major priority for the city as information technology rebuilt.

Brookville Equipment Corporation (BEC) of Pennsylvania was awarded the contract to provide the components to rebuild 31 New Orleans' streetcars to help the city bring its transportation infrastructure closer to full capacity. The streetcars were submerged in over five anxiety of water while parked in their machine barn, and all electrical components affected by the flooding had to be replaced.[14] BEC's engineering science and drafting departments immediately began work on this three-twelvemonth project to render these New Orleans icons to service. The trucks for the cars were remanufactured past BEC with upgraded drives from Saminco and new control systems from TMV Control Systems.[15] Painting, body work, and final assembly of the restored streetcars was carried out by RTA craftsmen at Carrollton Station Shops. As of March 2009, sufficient blood-red cars had been repaired to take over all service on the Culvert Street and Riverfront lines. As of June 2009, the last three Canal Street cars were scheduled for repair. The 7 Riverfront cars were worked on next; they began to return to service in early on 2010.[16]

Current lines [edit]

- The St. Charles Streetcar Line is the oldest continuously operating streetcar line in the world, having opened in 1835. Each machine operating on the line is a celebrated landmark. It runs from Canal Street all the way to the end of St. Charles Avenue at Due south Carrollton Artery, and then out South Carrollton Avenue to its final at Carrollton and Claiborne.

- The Canal Streetcar Line, which originally operated from 1861 to 1964 and which was rebuilt and reopened in 2004, runs the entire length of Canal Street, from well-nigh the Mississippi River to the cemeteries at Urban center Park Avenue. A branch streetcar line turns off of Canal Street into North Carrollton Artery to the entrance of City Park at Esplanade Avenue, most the New Orleans Museum of Art. Beginning July 31, 2017, and completed on December 4, a new loop terminal for the Cemeteries Branch was built north of City Park Avenue on Canal Boulevard, providing passengers with meliorate admission to transfer between the streetcars and connecting bus lines. Following a month of testing and training, the new loop went into service January 7, 2018.[17] [xviii] At times in the by, some Culvert cars have operated through on the Riverfront tracks from the French Market place terminal to Canal Street, before proceeding out Canal.

- The Riverfront Streetcar Line opened October 14, 1988, and runs parallel to the river from Esplanade Artery along the border of the French Quarter, past Culvert Street, to the Convention Eye in a higher place Julia Street in the Arts Commune.

- The Rampart–St. Claude Streetcar Line, opened on January 28, 2013, running along Loyola Avenue from New Orleans Matrimony Passenger Terminal to Canal Street, and was extended along Rampart St., McShane Pl., and St. Claude Artery to Elysian Fields Avenue effective October two, 2016. Prior to the extension, information technology was known as the Loyola-UPT Line and turned off of Loyola Avenue to run along Canal Street to the river, and on weekends on the Riverfront line tracks to the French Market. The line no longer operates down Canal Street to the river, nor offers weekend service on the Riverfront line.[9] The extension of the line to Elysian Fields Avenue was known as the French Quarter Rails Expansion and entailed building 1.5 mi (2.4 km) of runway with vi sheltered stops, and with track laid in the street adjacent to the neutral ground, similar the track for the original 2013 portion of the line. Preparation for structure began in December 2014, and a groundbreaking ceremony was held January 28, 2015 to begin actual construction.[9] [19]

Future Network Expansion [edit]

RTA has plans to extend the Rampart-St. Claude line past its present terminal at St. Claude and Elysian Fields to Press Street, and also downward Elysian Fields to the river to connect with the Riverfront line.[xx] These plans are not funded, and are on hold as more urgent needs are considered for funding.[21]

Current rolling stock [edit]

The last 19th century Ford Salary & Davis car (Ole 29), still in work car service on St. Charles Avenue, 2008.

The St. Charles Artery Line has traditionally used streetcars of the type that were common all over the Usa in the early parts of the 20th century. Most of the streetcars running on this line are Perley Thomas cars dating from the 1920s. The one exception is an 1890s vintage streetcar that is all the same in running condition; information technology is used for maintenance and special purposes. Unlike well-nigh Due north American cities with streetcar systems, New Orleans never adopted PCC cars in the 1930s or 1940s, and never traded in older streetcars for modern light track vehicles in the later 20th century. New Orleanians also continue to prefer employ of the term streetcar, rather than trolley, tram, or light rail.

In the Carrollton neighborhood, the RTA has a streetcar barn, called Carrollton Station, where the streetcars of the city's lines are stored and maintained. The cake wide circuitous consists of two buildings: an older machine barn at Dante and Jeannette Streets and a newer barn at Willow and Dublin Streets. The store there has become capable of duplicating any function needed for the vintage cars.[iv]

With the add-on of the new Riverfront and Canal lines, more vehicles were needed for the system. The RTA's shops built two groups of modernistic cars equally near duplicates of the older cars in appearance. One grouping of seven cars was built for the Riverfront line in 1997, and another group for the restored Canal Street line in 1999 (one car) and 2002–2003 (23 cars). The trucks for the 2002–2003 cars were manufactured by Brookville Equipment Corporation.[22] These new cars tin be distinguished from the older vehicles by their brilliant red color; unlike the older cars, they are ADA-compliant, and the Canal Street cars are air conditioned.

Earlier Hurricane Katrina, the historic cars ran exclusively on the St. Charles Avenue Line, and the newer cars on the other two lines. All the same, in the wake of hurricane impairment to the St. Charles line tracks and overhead wires, and to almost all of the new red cars, the older cars were run on Canal Street and Riverfront until the new cars could be repaired. Using any worked wherever information technology could exist run connected for several years. By 2010 plenty restored streetcars were dorsum in service to once again confine the historic Perley Thomas cars to the St. Charles line.

| Image | Model | Manufacturer | Constructed | In Service | Number built; in service | Seating Chapters |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 900 Series | Perley A. Thomas Car Works High Betoken, North Carolina[4] : 151–158 [23] | 1923–1924 | 1923–present | 73; 35 in electric current operation | 52 |

| 457-463 Series 900 Series Replicas | New Orleans Regional Transit Authority[22] [24] | 1997 | 1997–present | 7; 7 in current operation | 40 |

| 2000 Serial 900 Series Replicas | New Orleans Regional Transit Authority[22] [25] | 1999, 2002–2003 | 1999–nowadays | 24; 24 in current operation | 40 |

Historic lines [edit]

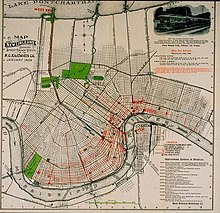

Map of New Orleans Showing Street Railway System of the New Orleans Railways Visitor, January 1904.

In the mid 19th to early on 20th century, the city had dozens of lines, including:[four] : Chapter 3

- Poydras-Magazine (January 1835 – March/Apr 1836) – Though brusk-lived, this was the first true streetcar line to begin operation in New Orleans, having opened the first week of January 1835.

- Jackson (January 13, 1835 – May xix, 1947) – This long-running line likewise opened before the St. Charles line, on Jan 13, 1835. Replaced with trolley bus and after diesel bus service.

- Louisiana (February 4, 1850 – 1878, Baronial 27, 1913 – December 27, 1934) – The original 1850–1878 Louisiana Line was a co-operative line of the New Orleans & Carrollton, running on Louisiana from St. Charles to the river at Tchoupitoulas. The later on 1913–1934 line ran from Canal Street up to Louisiana Ave. on Freret and Howard (now LaSalle) Streets, then to Tchoupitoulas. For part of its life, it terminated on Canal Street at the ferry landing.

- Napoleon (February iv, 1850 – February 18, 1953) – Similar the Louisiana Line, the original Napoleon Ave. line was a branch line of the New Orleans & Carrollton, running on Napoleon from St. Charles Ave. to the river at Tchoupitoulas. Dissimilar the Louisiana, it was extended to Canal Street when electrified in 1893. A second line, popularly known as the Royal Blueish Line, was opened on January ane, 1903 from St. Charles out to the end of the Avenue at Wide Street. The ii were combined in 1906. With the Shrewsbury Extension on Metairie Road, which operated from 1915–1934, this was the longest streetcar line in New Orleans. Its routing was equally follows: on Napoleon Ave. from Tchoupitoulas to S. Broad, and so turning right onto Due south. Broad, left onto Washington Ave. (running between the street and the Palmetto-Washington drainage canal), right onto Southward. Carrollton Ave., left onto Pontchartrain Blvd. (this would at present be impossible due to the presence of the Pontchartrain Expressway / I-x), left onto Metairie Rd., and so zig-zagging through several Old Metairie streets to a terminus at Cypress and Shrewsbury Rd. (now Severn Ave.).

Streetcar on Esplanade Avenue, 1921.

- Esplanade (June 1, 1861 – December 27, 1934) – This was the showtime streetcar line to traverse the "back-of-boondocks" section of New Orleans, running all the way out Esplanade Ave. to Bayou St. John in its original routing. From 1901–1934 the Canal and Esplanade lines operated in a loop as the Culvert-Esplanade Belt, until Esplanade Ave. went to buses in 1934.

- Coliseum (originally Canal and Coliseum and Upper Mag) (September 1, 1881 – May 11, 1929) – Known equally the "Snake Line" because it curved all over the place in uptown New Orleans. Originally operating on Coliseum Street from Culvert to Louisiana, it was extended piece by piece over the years, commencement on Magazine to the nowadays Audubon Park, so through the park to Broadway then across to Carrollton Ave., where information technology continued to the loop on Oak and Willow Streets from Carrollton to the Orleans-Jefferson parish line. Beginning in 1913, withal, the Magazine Line took over all trackage on Magazine Street, and a shorter Coliseum Line ended near Audubon Park.

- Mag (June viii, 1861 – February 11, 1948) – Its longest routing, in the 1910s, took information technology all the way from Canal Street, up Mag and Broadway to S. Claiborne Ave. Replaced with trolley bus and later diesel passenger vehicle service.

Prytania line streetcar, probably at Prytania Station carbarn, 1907.

- Prytania (June 8, 1861 – October ane, 1932) – Known as the "Silk Stocking Line", Prytania ran through the Garden District on its namesake street.

- Bayou Bridge and Urban center Park (mid-1861 – December 22, 1894, route absorbed into Esplanade line) – This early line ran the full length of the nowadays-day Urban center Park Ave. (then called Metairie Rd.).

- Tchoupitoulas (August 10, 1866 – July 2, 1929) – This early riverfront line in one case ran the total-length of Tchoupitoulas St. from Canal Street to Audubon Park.

- N. Claiborne (May 13, 1868 – December 27, 1934) – This was a downtown (i.e., downriver) line. From 1917 to 1925, it was operated as a single line with the Jackson Line.

- Tulane (originally Canal & Common) (January 15, 1871 – January 8, 1951) – From 1900–1951 the St. Charles and Tulane lines operated in a loop as the St. Charles-Tulane Belt, taking passengers past the beautiful homes on St. Charles Ave., up S. Carrollton Ave. by the St. Charles Line's nowadays terminal at S. Claiborne Ave., across the New Basin Canal (now the site of the Pontchartrain Pike), turning at the former Pelican Stadium onto Tulane Ave. and back downtown. The Tulane Avenue service became a trolley bus and after a diesel fuel motorbus route.

- Broad (originally Culvert, Dumaine & Fair Grounds) (1874 – July 16, 1932) – After 1915, the Broad Line had ii branches, on St. Bernard and Paris Avenues.

A Clio line streetcar in St. Charles Street, New Orleans Central Business Commune, 1920.

- Clio (January 23, 1867 - September one, 1932) - This line originally ran from Canal Street up St. Charles Street and over to Clio Street to Magnolia Street, returning on Erato and Carondelet Streets. In 1874, it was extended across Canal Street to Elysian Fields, making it the starting time streetcar line to cross Culvert Street. It was extended at both ends from time to time, earlier giving upward its territory to newer lines in 1932.

- Carondelet (July 29, 1866 - September 7, 1924) - This uptown line ran on its namesake street from Canal Street to Napoleon Ave. At its most all-encompassing, it also ran on Freret Street from Napoleon to Broadway, on trackage that somewhen became office of the Freret line, and information technology crossed Canal Street into the French Quarter, pioneering the route of the afterwards Desire line.

- Announcement (February 27, 1867 - December 23, 1917) and Laurel (August 12, 1913 - July 5, 1939) - These were uptown lines near the River, running on Annunciation and Chippewa Streets, and on Laurel and Constance Streets.

- W Terminate (Apr 20, 1876 – Jan 15, 1950) – This line is yet fondly remembered for its jaunty ride through the grassy right-of-mode forth the New Basin Canal (now filled in) to the popular West End surface area on Lake Pontchartrain.

- Castilian Fort (March 26, 1911 – October 16, 1932) – Farther east forth Lake Pontchartrain at the mouth of Bayou St. John was another amusement surface area congenital effectually an one-time fort. This was the original location of Pontchartrain Beach earlier it moved further due east to Elysian Fields Ave. The Spanish Fort Line branched off of the Due west End Line at what is now Robert Due east. Lee Blvd.

- South. Claiborne (February 22, 1915 – January five, 1953) – In its afterward years, this line operated at the edges of the neutral basis, which covered a large drainage culvert, part of which was open. The part of the neutral ground that was covered was planted in grass and ornamental trees and bushes, and was quite beautiful. Replaced by diesel fuel omnibus service.

- Desire (October 17, 1920 – May 29, 1948) – This line ran through the French Quarter down to its namesake street in the Bywater district. It was immortalized in Tennessee Williams' play A Streetcar Named Desire. The line was converted to buses in 1948.[26] Various proposals to revive a streetcar line with this name accept been discussed in recent years, but the New Orleans Regional Transit Say-so has no current plans to rebuild. Enthusiasts are nicknaming the new St. Claude line the "Desire line", despite the former and latter each having run on split up and distinct routes. For many years, a 1906 Brill-congenital semi-convertible streetcar was displayed in the French Market with a Desire route sign, although there is no bear witness that cars of this type ever served the Desire Line. At first it was under embrace; afterwards out in the open up, it deteriorated from the atmospheric condition, and in the 1990s it was turned over to New Orleans RTA. Information technology is currently housed at Carrollton Station in the car shops.

- Freret (September seven, 1924 – December 1, 1946) – Created from trackage formerly function of the Carondelet line. Replaced with trolley bus and subsequently diesel autobus service.

- St. Claude (February 21, 1926 – Jan i, 1949) – This and the Gentilly Line were the last two streetcar lines to open in New Orleans until the August 1988 inauguration of the Riverfront line. Replaced with trolley bus and later diesel bus service. The New Orleans Regional Transit Say-so has plans to rebuild a similar route.[27]

- Gentilly (February 21, 1926 – July 17, 1948) – Gentilly was derived from the former Villere Line. It was unusual in being named for the neighborhood information technology served, rather than the street along which information technology ran. At one end, information technology traversed the French Quarter. Then it turned up Almonaster (at present Franklin) to its outer terminal at Dreux. Replaced by diesel omnibus service, which was eventually renamed Franklin for the street.

- Orleans/Kenner interurban (or O.K. Line) – This line operated between 1915 and 1931 and connected New Orleans to Kenner. It began at the intersection of Rampart and Canal in New Orleans and followed the Tulane streetcar line to the intersection of South. Carrollton with S. Claiborne, then proceeded along the route of the present-twenty-four hour period Jefferson Hwy. through Jefferson Parish to the St. Charles Parish Line in an expanse then known as Hanson City (now part of Kenner). This line was not a NOPSI service, although it came under NOPSI control in the belatedly 1920s.[28]

Preserved streetcars [edit]

In addition to the 35 Perley Thomas-built 900-series streetcars that serve the St. Charles line, the following New Orleans streetcars have been preserved in various ways.[29] [five] : 26–32

- Preserved in New Orleans

453: The final of the 25 Brill semi-convertible cars. It was on display at the French Market and subsequently at the Mint, only exposure to the weather caused its deterioration. It is known in posed pictures every bit the Streetcar Named Desire, although there is no evidence that this class of streetcar e'er ran on the Desire line. It is currently stored inoperative at Carrollton Station, but it could exist restored for operation.

919 and 924: These two Perley Thomas cars, originally twins to the 35 900-series cars running on the St. Charles line, were sold in 1964 when the Canal line was discontinued. They were bought back by RTA in 1985 and refurbished for service on the Riverfront line, beginning August 14, 1988. They were given Riverfront automobile numbers 451 and 450, respectively. They were once again retired in 1997 when the Riverfront line was re-equipped with new cars 457-463. They are currently stored inoperative at Carrollton Station, only they could exist restored for operation.

957: When the Culvert line was discontinued in 1964, this machine was sold to the Trinity Valley Railroad Social club in Weatherford, Texas, west of Fort Worth. Then information technology was sold to the Spaghetti Warehouse Company, then to McKinney Artery Transit Authorisation in Dallas, Texas, and finally information technology was purchased by New Orleans RTA in 1986. It was stored until 1997, when it was rebuilt with a wheelchair lift and modern controls, becoming the showtime of the new 457-463 series cars for the re-equipment of the Riverfront line.

- Preserved for revenue operation in San Francisco

952: This Perley Thomas car was sold in 1964 when the Canal line was discontinued, and was bought dorsum past RTA in 1990 and refurbished for service on the Riverfront line. As number 456, it served Riverfront until 1997. After its second retirement, it was rebuilt in the aforementioned mode as the 35 St. Charles line cars, given its original number, and sent on long-term loan to the San Francisco Municipal Railway, where it operates on that city's E-Embarcadero and F-Market & Warves lines as role of the Heritage Fleet.

913: This machine was sold to the Orange Empire Railway Museum in Riverside County, California in 1964 when the Canal line was discontinued. Later, information technology was sold to San Francisco Municipal Railway to augment service there by car 952. And then far, it has non been refurbished for service, only is stored for future use.

- Preserved at museums and heritage operations

832: At Pennsylvania Trolley Museum at Washington, Pennsylvania.

836: At Connecticut Trolley Museum at Warehouse Point, Connecticut.

850: At Shore Line Trolley Museum at Branford, Connecticut.

These are the last three 800-series cars in existence. All were congenital past Perley Thomas in 1922. The museums take restored all three to like-new status, and operate them on museum property.

918: Now at North Carolina Transportation Museum, Spencer, NC, intended for cosmetic restoration. For a time, it was stored at Thomas Congenital Buses, the current proper noun of its builder, Perley Thomas Car Co.

966: Endemic past Seashore Trolley Museum, Kennebunkport, Maine, and operated at Lowell National Historical Park, Massachusetts.

References [edit]

- ^ Henry, Lyndon (February 2007). "Rapid Streetcar: Rescaling Design and Cost for More Affordable Light Rail Transit". Light Rail Now Project. Retrieved April ix, 2014.

- ^ "Streetcars in New Orleans". NewOrleansOnline.com. The Official Tourism Site of the City of New Orleans. 2013. Retrieved July 16, 2013.

- ^ "Public Transportation Ridership Report First Quarter 2015" (PDF). American Public Transportation Association. May 27, 2015. p. 3. Retrieved Baronial 21, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j thou l m n o p q r s t u 5 w 10 y Hennick, Louis C.; Charlton, Due east. Harper (1975). The Streetcars of New Orleans. Jackson Foursquare Press. ISBN978-1565545687.

- ^ a b c d Hampton, Earl W. (2010). The Streetcars of New Orleans 1964-Present. Gretna, Louisiana: Pelican. ISBN978-1589807310.

- ^ Bardes, John (Apr 28, 2018). "The New Orleans Streetcar Protests of 1867". We're History . Retrieved Dec thirty, 2020.

- ^ Streetcar Protest 1867, April 28, 1867.

- ^ Confederate Transit Marriage Staff (1992). A History of the Confederate Transit Marriage. Washington, DC: Amalgamated Transit Union.

- ^ a b c "Fall Service Changes for Bus And Street Car Lines". Retrieved September 14, 2016.

- ^ Reid, Molly (Nov x, 2007). "Fanfare greets streetcar'south return to part of Uptown". NOLA.com. NOLA Media Group. Retrieved Apr 9, 2014.

- ^ Eggler, Bruce (December 22, 2007). "St. Charles streetcar route to grow again Dominicus". NOLA.com. NOLA Media Group. Retrieved April nine, 2014.

- ^ Faciane, Valerie (June 22, 2008). "Back on line: Streetcars render to South Carrollton". NOLA.com. NOLA Media Group. Retrieved April 9, 2014.

- ^ "St. Charles Streetcar Line Update". New Orleans Regional Transit Authorization. 2008. Archived from the original on Oct xiv, 2008. Retrieved April ix, 2014.

- ^ "Repairing New Orleans' Streetcars". Mass Transit. October 5, 2011. Retrieved April 9, 2014.

- ^ Hennick, Louis. "Appendix 3 to The Streetcars of New Orleans". Retrieved August x, 2015. Page aa.

- ^ Friedman, Jr., H. George. "Canal Street: A Street Railway Spectacular, Part 5". University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Retrieved June 19, 2018.

- ^ "Cemeteries Transit Center Project". New Orleans RTA . Retrieved October 7, 2017.

- ^ "Canal streetcar to cross over Metropolis Park Avenue starting Sunday". New Orleans RTA . Retrieved January 8, 2018.

- ^ "Despite Lawsuit New Orleans Streetcar Project on North. Rampart, St. Claude Gets Underway". nola.com . Retrieved January 29, 2015.

- ^ "St. Claude and Elysian Fields Streetcar Extensions, New Orleans, Louisiana". U. S. Department of Transportation. May 2018.

- ^ Evans, Beau. "Rampart-St. Claude streetcar extension study could move into irksome lane". nola.com . Retrieved February twenty, 2021.

- ^ a b c Lietwiler, C. J. (Dec 2004). "New Orleans: Streetcars render to Canal Street". Tramways & Urban Transit. Hersham, Surrey, UK: Ian Allan Publishing/Low-cal Rails Transit Association. pp. 452–456.

- ^ Hennick, Appendix III, pp. x–z.

- ^ Hennick, Appendix 3, p. aa.

- ^ Hennick, Appendix Three, p. bb.

- ^ "Bus Line Replaces Street Motorcar 'Desire'". The New York Times. United Press International. May 31, 1948. p. 12.

- ^ "Loyola Projection Alternative Analysis". New Orleans Regional Transit Potency. Archived from the original on December 8, 2010. Retrieved April ten, 2014.

- ^ Hennick, Louis C.; E. Harper Charlton (1979). Street Railways of Louisiana. Pelican. pp. 106–115. ISBN0-88289-065-four.

- ^ Hennick, Appendix III, pp. w, y, z, aa.

- American Society of Mechanical Engineers, St. Charles Avenue Streetcar Line Brochure

- U.S. Urban Rails Transit Lines Opened From 1980 (PDF)

- NYCSubway.org's New Orleans pages

External links [edit]

Route map:

KML is not from Wikidata

- New Orleans Regional Transit Potency

- New Orleans - St Charles Streetcar - 1920s Perley Thomas 900 3D Model of Streetcar

- Interactive map of New Orleans streetcar network

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Streetcars_in_New_Orleans

Post a Comment for "When Will the Trolley From Upoerline to Tulane Run Again Innew Orleans"